Members of the 1972 U.S. Olympic men’s basketball team have talked about finally retrieving those silver medals they vowed to never accept and left behind in Germany.

No, they still don’t want them for themselves.

They believe the medals belong in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, but the latest attempt to get them from the International Olympic Committee has been thwarted.

To get the medals a home in the Hall of Fame — which is holding its induction ceremony for the Class of 2022 this weekend — the IOC told the players they first have to accept them.

“If we have to accept them, then that’s not going to be an option,” said Tom Burleson, a center from North Carolina State who played on the team.

It’s the same non-starter it was 50 years ago Friday.

The Americans’ first loss in Olympic competition remains one of the most complicated and controversial finishes ever — there’s little question it’s part of the sport’s history, which the Hall preserves.

It’s not that the IOC disagrees with the Hall of Fame option. The Olympic governing body would let members of the team do what they want with the medals — once they’ve followed the organization’s procedure for obtaining them.

Tom McMillen, a forward from Maryland and a member of the 1972 team, said the IOC saying players having to accept the medals is “sort of ridiculous” and came up with a possible solution to the impasse: Have a third-party accept the medals so they could be placed in the Hall of Fame.

“What we talked about was, given what the IOC’s position is, we could say, ‘OK, give us the medals,’ and then we reject them by giving them to the Naismith museum,” said McMillen, now president and CEO of the LEAD1 Association, representing college Football Bowl Subdivision athletic directors and programs.

“In other words, we say, ‘We don’t want these, we don’t think we deserve them, we think we deserve the gold,’” McMillen said. “But I think everybody’s got different views. I mean, it’s really hard, so it’s probably going to stay the way it is.”

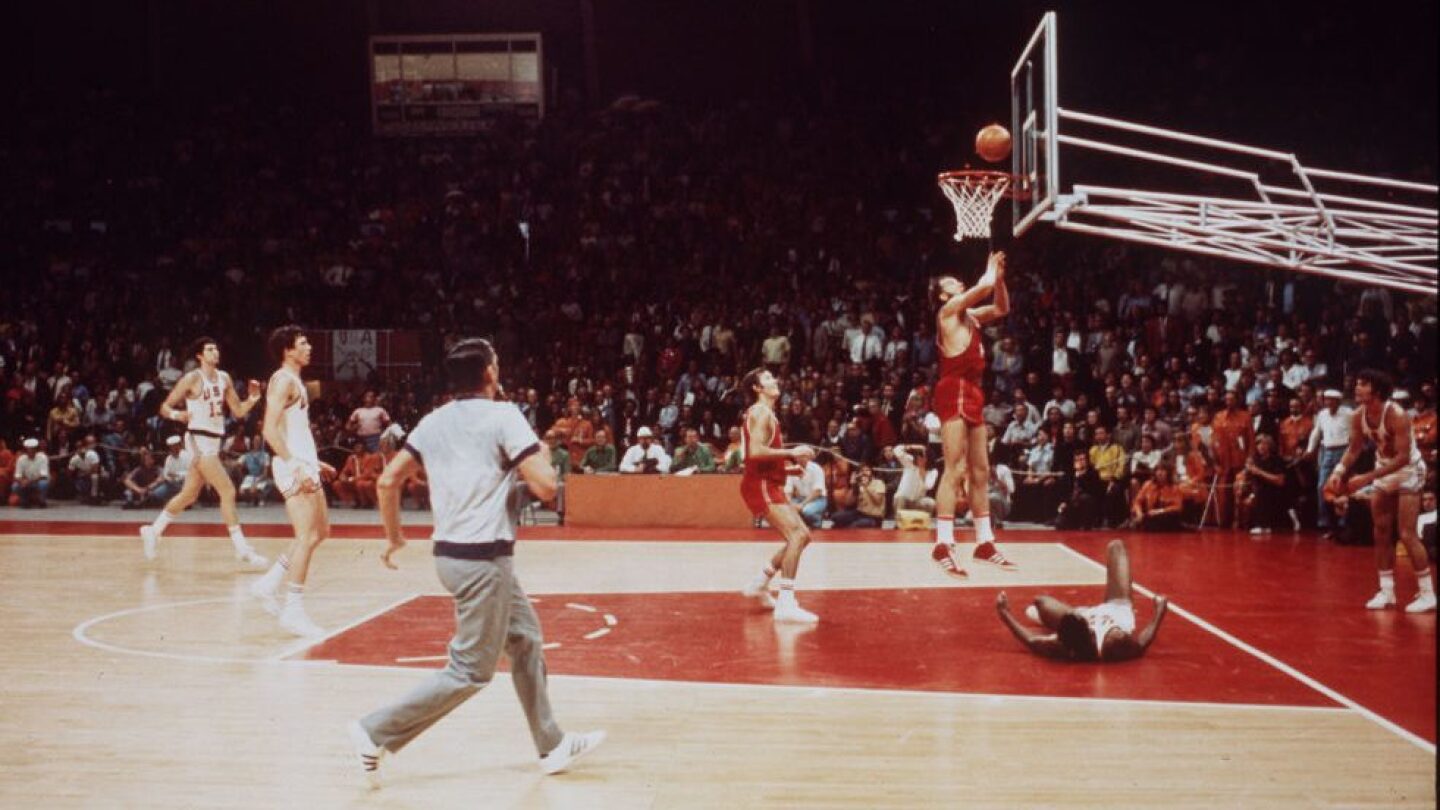

Today is the 50th anniversary of the most controversial Olympic game ever- the US vs Soviet basketball game at the Munich '72 Olympics. Here I am celebrating our win and then the refs took the game away from us. Till this day, we have never accepted the silver medals. pic.twitter.com/UkxD12RwoI

— Tom McMillen (@TomMcMillen611) September 9, 2022

At least for the foreseeable future.

The sting of the loss still lingers.

The United States brought a 63-game Olympic winning streak into the final against the Soviet Union on Sept. 9, 1972, in Munich. It appeared the Americans had extended it to 64 when the horn sounded to end the game with them leading 50-49.

The game was restarted — twice — during what even the players struggle to define as errors by the officials or an outright attempt to cheat them.

Referees initially put time back on the clock after the Soviets argued they had called a timeout and the horn had sounded. The clock was still being reset when the ball was put into play and the Soviets didn’t score, so R. William Jones, the secretary general of FIBA, again ordered the clock reset to 3 seconds.

Given another chance, the Soviets fired a long pass to Aleksander Belov, who scored to give the Soviets a 51-50 victory.

Ed Ratleff, a forward who played at Long Beach State, believes it’s possible some players may have softened on their stance after 50 years, but said neither he nor anyone he still talks to has. One of them, Kenny Davis, has in his will that his family is to never accept silver.

“I tell you what, I am the same way I was 50 years ago,” Ratleff said. “My mother always taught me you won’t take anything that doesn’t belong to you, and I didn’t think the silver medal belonged to us.

“I’m not taking it and I’m sure 100% we got cheated out of it and I think they knew that, too.”

McMillen hopes the entire team will one day be enshrined in the Hall of Fame and with this being the 50th anniversary of the Munich Games, this weekend would have been a fitting time. It’s an honor Olympic champions such as the 1960 and 1992 U.S. teams have earned.

Short of that, he hoped at least the medals could have a home in the Springfield, Massachusetts, museum. McMillen, a former Congressman from Maryland, asked IOC member Dick Pound about putting the medals in the Hall of Fame.

The IOC let McMillen know earlier this year — and reiterated its position again this week — that nobody could accept the medals except the players themselves.

“The IOC expressed its appreciation for his efforts but felt that appointing an attorney to accept the medals would not be appropriate,” an IOC spokesman said Thursday in an email to The Associated Press.

Previous conversations about awarding dual gold medals also had been denied and McMillen was disappointed to learn his latest attempt wouldn’t work, either.

Given that, McMillen said the medals might still be in a vault in Switzerland in 1,000 years, but in fact they’re not even all together now. The IOC said it received seven medals in 1992 from the local organizing committee, which are now kept in its Olympic Museum collections. The others remained with the organizing committee.

Jerry Colangelo, chairman of the Hall of Fame board, said the Hall is aware of the players’ wishes and would like to help them. However, it appears those steps are out of the Hall’s hands.

“There’s a scar on the hearts of each one who has participated,” said Colangelo, also the former chairman of USA Basketball, adding that any decisions will have to wait.

“It still needs to be addressed as it pertains to the Hall of Fame.”

There have been attempts to heal the scar, or at least ease the pain of the loss for players.

During the 2008 Olympics, the next generation of stars – NBA standouts make up Olympic teams now, unlike the college players in 1972 – went over to the broadcast table to acknowledge Doug Collins, whose free throws with 3 seconds left had given the Americans the lead in 1972, and they believed, the victory, after he worked the gold-medal game at the Beijing Games.

Four years later, members of the team held a 40th reunion, where they remained united that there would never be accepting of silver.

Two of them, James Forbes and Dwight Jones, have since died. McMillen hoped there was a way to get the rest together sometime this year, though it seems there would be no change given what they’ve heard from the IOC.

“We’ll just let them keep it,” Burleson said. “I hate it, it would be nice to think they were on U.S. soil somewhere. But then again, if they want them, they can keep them.”

OlympicTalk is on Apple News. Favorite us!